-

“A social history of steam power, covering not just railways, but also the use of steam engines to power everything from cotton mills to lawnmowers.”

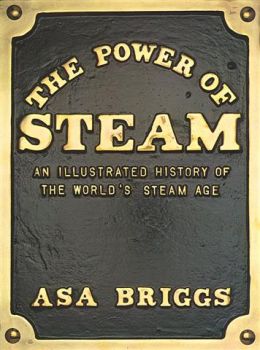

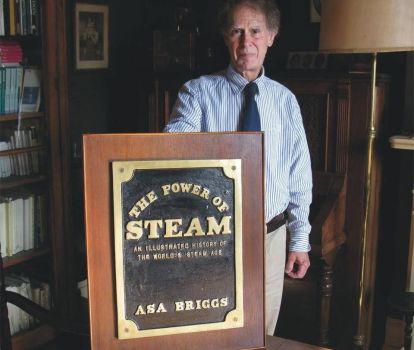

The Power of Steam

An Illustrated History of the World’s Steam Age

By Asa Briggs

$40.00

The eminent historian Asa Briggs tells the story of steam power from its beginnings in the ancient world through to the vintage steam preservation movement of the present day. The book describes and illustrates both railways, the iron horses of the steam age, and the many other forms of steam engine from giant pumping stations down to steam-powered lawn mowers. It also contains more than 200 illustrations and historic photographs.

- RRP: £25.00

- Format: 253 x 188 mm (10 x 7 1/2 in)

- Pages: 208 pages

- Pictures: 200 plus, b/w and colour

- Binding: Hardback with jacket

- Rights available: All except UK and US

- ISBN: 978-1-873329-00-9 >

- Publication: 1990

An Illustrated History of the World’s Steam Age

Asa Briggs examines the power of steam from every angle, describing its impact first on Britain and then on the rest of the world. He introduces many familiar figures – George Stephenson driving his Rocket to victory at the Rainhill Trials, George H. Corliss starting his famous 1,400-horse-power engine at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition and Charles Parsons startling the admirals with his high-speed Turbinia at the Spithead Naval Review. But he also tells us what Karl Marx thought about steam engines, how Dickens and Charlotte Brontë, Mark Twain and Walk Whitman reacted to a smoke-laden, steam-driven world, and even, in verses entitled ‘The Steam Loom Weaver’, how steam power could be incorporated into the poetry of love. We learn how steam not only had the power to drive machines but to alter the natural environment and transform human thought, politics, society and culture. The book contains more than 200 illustrations, including many historic photographs never published before, and a gazetteer highlighting the places in Britain, the United States and other countries where working steam engines may be seen and enjoyed.

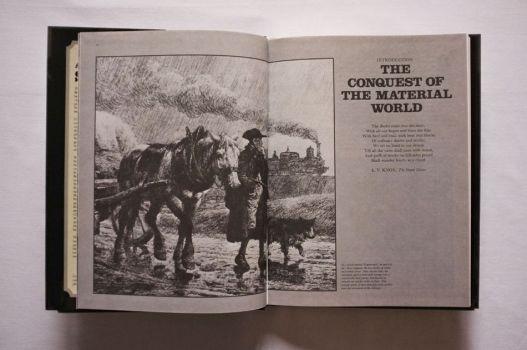

INTRODUCTION

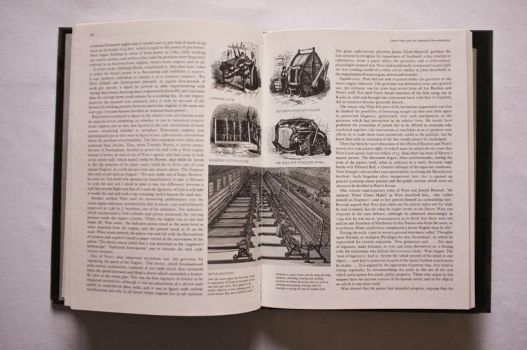

CHAPTER 1: MAKING STEAM WORK

CHAPTER 2: JAMES WATT AND THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

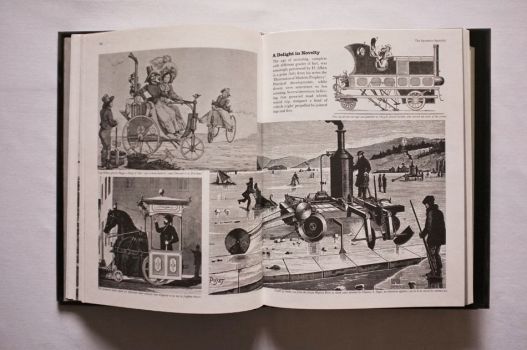

CHAPTER 3: THE GOSPEL OF STEAM

CHAPTER 4: LOCOMOTION

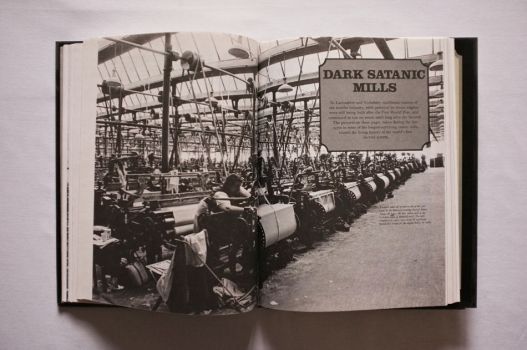

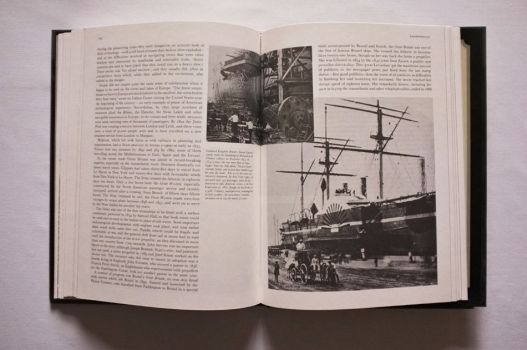

CHAPTER 5: POWER FOR THE WORLD

CHAPTER 6: VINTAGE TECHNOLOGY

NOTES ON SOURCES

PLACES TO SEE STEAM

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Asa Briggs was born at Keighley, Yorkshire, in 1921 and took his first degree in History and Economics. In the course of a distinguished career, he was Professor of Modern History at Leeds University (1955-61) and Professor of History at the University of Sussex, where he was Vice-Chancellor from 1967 to 1976.

His main field of interest was the social and cultural history of the 19th and 20th centuries, on which he wrote many books, including The Age of Improvement, Victorian People, Victorian Cities, Victorian Things, A Social History of England and a four-volume history of broadcasting.

Lord Briggs was made a life peer in 1976 and became Provost of Worcester College, Oxford, later that same year. At the age of 92 he published his final book, Loose Ends and Extras, in which he reflects on our relationship with time. Lord Briggs died in March 2016 at the age of 94. He is survived by his wife Susan Banwell and their four children.

FUN OF THE FAIR

From the 1870s until after the First World War, fairgrounds were enlivened by the smell of coal smoke, the blare of organs and the sheer exhilaration of steam-powered rides on scenic railways, gondolas, dragons and gallopers.

Many rides had centre engines with chimneys projecting from the big-top awnings. Others were powered electrically by showman’s engines with dynamos and extended chimneys to keep smoke off the customers and the varnished paintwork of the rides. John Evan’s live-rail dragon scenic was typically elaborate. It used two engines, one to drive the cars (each weighing two tons and carrying 12 people), the other to power the organ, the lights and the centrifugal pump that kept water flowing down the steps of a painted waterfall decorated with real ferns.

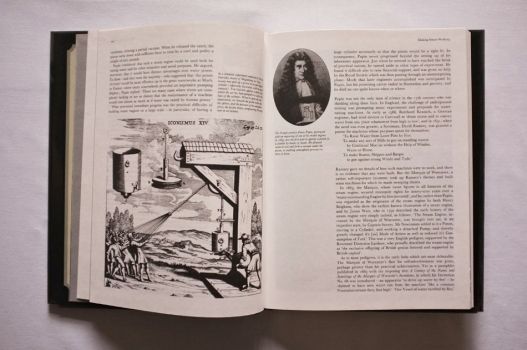

JAMES WATT AND THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The name of the Scots engineer James Watt was and still is to many people virtually synonymous with the steam engine, and the mistaken belief that he invented the steam engine long enjoyed popular currency. Watt’s reputation rose so high among the Victorians that when the Lord Provost of Glasgow, Sir James Bell, wrote a history of his great city in 1896, he found it a matter of pride to begin with the achievement of Watt.

‘According to tradition,’ Bell’s first paragraph starts, ‘it was while taking his accustomed walk on Glasgow Green on a pleasant evening in the spring of 1975 that the idea of the separate condenser to the steam engine flashed across the mind of James Watt. Every circumstance connected with that conception was momentous and memorable. No innovation, in any time or country, was fraught with such far-reaching and revolutionary consequences in the economic and social relations of the human race.’

The separate condenser to which Bell referred was the biggest single improvement ever made to the steam engine. By condensing the steam in a separate chamber rather than in the cylinder itself, Watt was able to create a far more efficient steam engine than Newcomen’s. To exploit his invention commercially, he joined the leading Birmingham manufacturer Matthew Boulton in 1774, forming one of the most celebrated partnerships in world economic history.