-

“A prestige book by a leading graphic designer and a popular railway writer.”

-

“Logan brings together for the first time a history of the corporate liveries of the American railroad that paved the way for today’s branding industry. An absolutely glorious book and a must-have for any engineer interested in trains.”

-

“Overall, it is a distinctive and visually rewarding catalogue of the power and beauty of advertising art, which moves elegantly between themes and eras as seamlessly as the iconic American trains with their decorated box cars it depicts.”

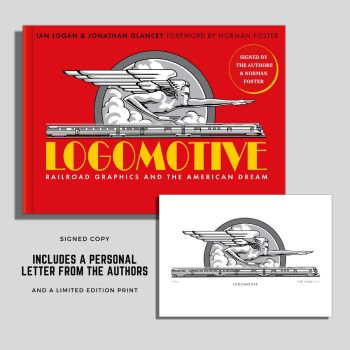

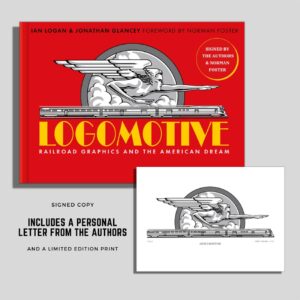

Logomotive Triple Signed Edition

Railroad Graphics and the American Dream

By Ian Logan & Jonathan Glancey, Foreword by Norman Foster; signed by all three

$125.00

This collector’s edition of Logomotive has been signed by three leading figures of design. Norman Foster is the architect of London City Hall, the Gherkin, the Reichstag Dome and train stations including Canary Wharf. Ian Logan created fabrics for Mary Quant and Jeff Banks and designed Biba’s iconic wallpaper. Jonathan Glancey was design editor of The Guardian and The Independent and is now a broadcaster and journalist for the Daily Telegraph, magazines and websites.

- Book Specifications:

- RRP: £80.00

- Format: 187 mm x 264 mm (7 2/5 x 10 2/5 in) landscape

- Pages: 272

- Weight: 1.3 kg (2 lb 14 oz)

- Pictures: 400 in colour

- Binding: Hardcover no jacket

- ISBN: 978-1-873329-50-4

- Publication: December 2020

- Print Specifications:

- RRP: £15.00 (free with triple signed copy)

- Format: 210 mm x 297 mm (A4)

- Paper: Hahnemuhle Photorag 308 g

- Weight: 20 g (0.7 oz)

- ISBN: 978-1-873329-64-1

- Publication: December 2020

Americana enthusiasts

One thing unites the authors of Logomotive: a passionate belief in the quality and vigour of American mid-century modern design. The architect Norman Foster, the Swinging Sixties designer Ian Logan and the architectural critic Jonathan Glancey joined forces to write this book about American railway logos, and all three have signed this limited edition of eight copies. With the book comes a limited-edition print of the cover image, drawn for Logomotive by the artist Neil Gower, and a personal letter from Ian and Jonathan. This is a slice of history.

Logomaniac

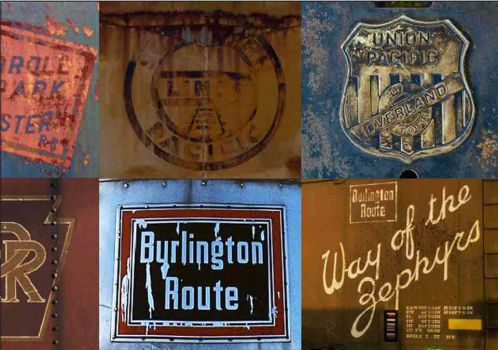

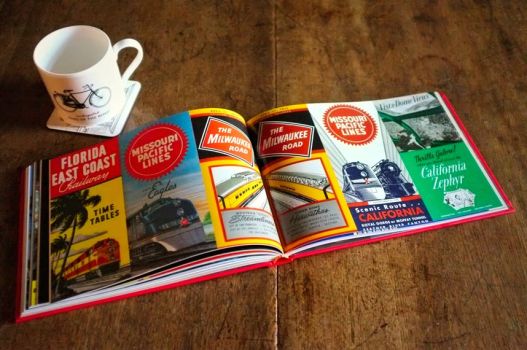

Whenever Ian Logan, or ‘the Tin Man of design’ as he was nicknamed by Terrence Conran, could get away from designing fabrics and wallpapers or tins for his own shop, he would escape to America. Wandering into stations and freight yards, he photographed the logos and slogans on locomotives and rolling stock and collected timetables, matchbooks and any other railway-related material he could lay hands on. He has selected 400 items from his impressive collection to illustrate Logomotive, including enamel signs he designed himself to commemorate some of his favourite railroads and passenger expresses.

Train-driving historian

Jonathan Glancey’s obsession with trains began in childhood as he pored over picture books on rainy days or went to see Merchant Navy class locomotives at the big London stations. This eventually led him to drive a variety of engines, most memorably an Indian Railways WP-class Pacific steam locomotive from Delhi to Chandigarh. His passion has inspired four books, The Train: A Photographic History, John Betjeman on Trains, Tornado: 21st Century Steam and Giants of Steam, in addition to the Channel 4 mini-series Small Railway Journeys. No one was better qualified to write the history behind Ian’s imagery in Logomotive.

Loco-spotting architect

How many know that the design interests of Norman Foster run to cars, planes and trains? Meet Norman Foster the one-time loco spotter, classic car collector, lover of period Americana. He spent much of his childhood by the tracks behind his home in Manchester ticking off the express trains as they powered past. He has designed train stations around the world, including Canary Wharf, and has now brought his expertise to the Foreword of this book, making him the third ‘namer’ on Logomotive.

FOREWORD BY NORMAN FOSTER

PREFACE: Ian Logan on his love for US railroads

CHAPTER 1: CONQUERING THE CONTINENT

How railroads reached all corners of the continent; transcontinental lines; infrastructure and rolling stock.

Setting a Style

Overland Brands

Spirit of the Union

Romance of the Southwest

Mountain Mascot

A Mighty Good Road

Across the Divide

Southern Blues

Multiple Identities

CHAPTER 2: A SENSE OF PLACE

Regional and local networks, and how they ran across one another’s lines.

Pride in Their Roots

Maritime and Coastal

Chicago and the Lakes

Southern Connections

Commuter Lines

CHAPTER 3: ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURES

The city as railroad hub: stations, freight yards and transfers.

Architectural Logos

Station Design

Romanesque Revival

New Deal Deco

Spanish Mission Style

Carrying the Message

CHAPTER 4: SELLING THE DREAM

How the railroads built customer loyalty through advertising campaigns, slogans, nicknames and branding.

The Soft Sell

Nicknames

Slogans

Native American Imagery

Logo Evolution

Union Pacific

New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroads

The On-Board Experience

CHAPTER 5: STREAMLINE STYLE

The influence of European Modernism and sleek Art Deco styling; innovative railroad design from the 1930s to 1950s.

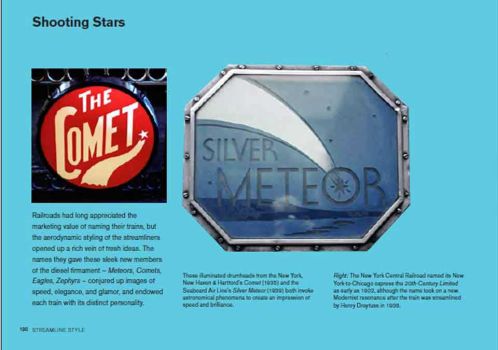

Shooting Stars

Eagles

Zephyrs

Hiawathas

The Aerotrain

Interiors

Art Deco Typography

On the Road

CHAPTER 6: PHOENIX ARISING

The switch from steam to diesel in the mid-20th century; the decline of passenger travel leading to amalgamations and Amtrak-operated services in the 1970s; the revival of restored steam locomotives on scenic routes.

Rust to Rust

Romance Revived

Heritage Line Logos

New Identities

Logo Revolution

New Haven

Canadian National

I Love G&W

Business Attire

Flying the Flag

FRONT-WINDOW VIEW

A Journey with Ian Logan on the Union Pacific

Railroad Patches

A RAILROAD GLOSSARY

RAILROAD NAMES, ABBREVIATIONS AND NICKNAMES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PICTURE CREDITS

INDEX

Ian Logan was at the centre of the design revolution that marked the end of post-war austerity. He studied at the Central School of Art and Design in London (now Central St. Martin’s), and won a scholarship to the Konstfack, Stockholm’s University of Arts, Crafts and Design. In the early 1960s he joined JRM Design, a fabric print company set up by a group of Central graduates in an almost derelict building in London’s East End. Ian and his partners produced prints for up-and-coming fashion designers such as Mary Quant and Jeff Banks, and designed a tin tray with a Middle Eastern-inspired motif that became enormously successful, first in Carnaby Street and then all over the UK.

Ian Logan was at the centre of the design revolution that marked the end of post-war austerity. He studied at the Central School of Art and Design in London (now Central St. Martin’s), and won a scholarship to the Konstfack, Stockholm’s University of Arts, Crafts and Design. In the early 1960s he joined JRM Design, a fabric print company set up by a group of Central graduates in an almost derelict building in London’s East End. Ian and his partners produced prints for up-and-coming fashion designers such as Mary Quant and Jeff Banks, and designed a tin tray with a Middle Eastern-inspired motif that became enormously successful, first in Carnaby Street and then all over the UK.

In the mid-1970s he set off in a new direction. Inspired by decorative Victorian tin boxes, he produced a range of tins for Harrods, Fortnum & Mason, Whittard of Chelsea and the National Trust. Commissions came from France, the Netherlands and the United States, for which he developed the Americana range featuring diners, gasoline stations and collectable cars. His money boxes in the form of the iconic red British telephone kiosk became known all over the world.

The journalist, author and broadcaster Jonathan Glancey is a trailblazing commentator on architecture and design, writing about buildings, cars, planes and trains with deep knowledge and infectious enthusiasm. The architecture and design editor of The Guardian from 1997 to 2012, he now reports on those topics for the Daily Telegraph, magazines and websites.

Norman Foster, Baron Foster of Thames Bank, Kt, OM, RA, is an internationally renowned architect whose buildings include the Hearst Headquarters in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Swiss Re ‘Gherkin’ in London and the Reichstag dome in Berlin. His passion for railways goes back to childhood, when he would watch trains passing his home in Manchester. He has undertaken several major railroad projects, including the Florence High Speed Station in Italy and four stations for the Haramain High Speed Rail in Saudi Arabia.

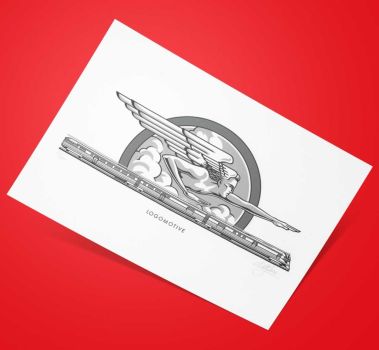

Neil Gower is an internationally acclaimed graphic artist who uses a range of styles and media. He is famed for his witty book jackets for authors such as Bill Bryson and William Golding and has created over 100 binding designs for The Folio Society. His art can be seen in works issued by houses in the UK and the US, as well as in a plethora of magazines, including The Economist, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. He was commissioned to draw the cover art of Logomotive by the book’s art director, Bernard Higton.

FOREWORD BY NORMAN FOSTER

Logomotive touches on so many of my personal interests and in the ways they connect, particularly the age of streamlining, which ushered in the new era of lightweight, stainless steel post-steam expresses like the Burlington Zephyr built by Budd of Philadelphia and Union Pacific M10000. Budd also pressed body panels for the revolutionary Chrysler Airflow automobile of the same period. In promotional photo shoots, the Airflow appears alongside the M10000. Significantly, both are also visually linked to the Art Deco detailing of the New York Chrysler Building – all born in the early 1930s.

FROM CHAPTER 3: ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURES

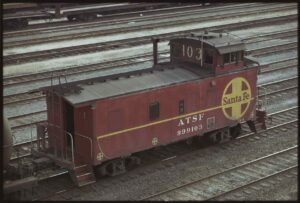

An epiphany of clanging bells, chiming whistles, baritone hooters and the percussive ministry of air-brake pumps announced the arrival of generations of trains at railroad stations across the United States. It was as if religious processions were coming to town. And, in a sense, they were. For the American railroad station or depot was, as medieval parish churches had been in Europe, the ritualistic hub around which life turned, especially in remote settlements.

As trains drew in, stations burst into life. Station wagons, horse powered before 1900, met passengers and their luggage bound for hotels. The station telegraph would be busy with reports on the line ahead and messages to and from passengers and their points of departure. Freight and baggage were manhandled in and out of boxcars and cabooses…

Station styles

By 1900, American passengers might find themselves boarding or alighting trains at stations designed in the guise of Romanesque abbey churches, Greek temples, imperial Roman baths, Gothic cathedrals, medieval cloth halls, Italianate palazzi, French chateaux, Black Forest gingerbread houses, Spanish missions and homespun farmsteads. Through this encyclopedia of styles, US railways expressed their values and ambitions. Station design could also be a reflection of local architectural character. Daniel Burnham’s mighty Union Station in Washington DC, opened in 1907, is an equal match for the Neoclassical civic temples and monuments lining the city’s Mall.

Classical allusions

For many Americans, the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome embodied republican and democratic virtues. Commanding a vista of streets and avenues fanning out from Columbus Circle, Union Station is fronted by a giant reiteration of the Arch of Constantine. Through this Neo-Roman portal as many as 200,000 passengers a day have flocked into the Great Hall behind it, the imperious design of which is based on the Baths of Diocletian. ‘Make no little plans,’ Burnham said. ‘They have no magic to stir men’s blood.’

FROM CHAPTER 1: CONQUERING THE CONTINENT

The 1881 Trademark Act made a significant visual impact on US railroads as draughtsmen got to work on new insignia. That same year the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy registered the first railroad trademark, a distinctive rectangle enclosing the legend ‘Burlington Route’ created by Daniel Lord of the pioneering Chicago advertising agency Lord & Thomas. Lord’s logo stayed firmly in place on Burlington Route trains until the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy merged with three other railroads in 1970 to form the Burlington Northern.

Choose a memorable logo

Also in 1881 the Union Pacific abandoned its antique-looking mountain elk symbol that might have belonged to any number of western railroads in favour of a distinctive shield design invented by its passenger agent Edward L. Lomax. With a number of subtle changes – among them the adoption of the colours of the US flag in 1888 and Futura-style lettering in the 1940s – this has stayed much the same ever since. Lomax said that it took him a year and a hundred sketches to find the exact right design.

By 1883, the Pennsylvania Railroad had begun using its famous and long-lived keystone emblem, a visual reference to the state’s nickname The Keystone State. By this time, the Pennsy was not just the largest US railroad, but the world’s biggest corporation. The Baltimore & Ohio offered a white-on-blue image of the dome of the US Capitol entwined with the letters B and O encircled by the legend All Trains Run Via Washington.

The Santa Fe’s cross-in-a-circle logo, allegedly created in 1880 by J. J. Byrne, the railway’s traffic manager, toying creatively with a pen and a silver dollar, was adopted in 1901, while the Great Northern’s Rocky Mountain goat trademark leapt from the mind of the railroad’s then Vice President W. P. Kenney in 1921. The Great Northern had played a key role in founding the Glacier National Park, where Rocky Mountain goats were a familiar sight. The beaver pelt trademark of the Rock Island – Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad – emerged in adverts in 1900 and had been refined into a well-known and enduring logo within five years.

Use your trademark

As early as 1890 Edward O. McCormick, general passenger agent of the Big Four system – the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway formed from a merger of four railroads in 1889 – gave a talk on railway advertising. ‘Have a trade mark and use it,’ he said. ‘Use it every-where . . . put it on your freight cars and plaster it wherever you can. People will unconsciously learn it, and will recognise it wherever it may be.’

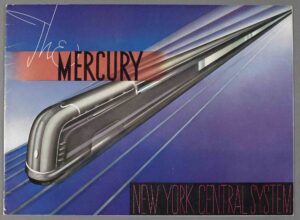

FROM CHAPTER 5: STREAMLINE STYLE

What these German, British and American trains had in common, whether steam or diesel, was a fresh look that manifested itself in bright new colour schemes, the latest in exterior styling and interior design, up-to-the-minute graphics, badges and logos, underpinned by decidedly modern advertising and marketing campaigns that helped sear their image into the popular imagination.

Gods and goddesses

The Burlington Zephyrs were the product of the research and imaginative skills of the aeronautical engineer Albert Dean, the advanced welding techniques of Edward Budd, the design flair of architects Paul Philippe Cret and John Harbeson and the vision of Burlington’s dynamic president, Ralph Budd. Wanting his streamliners to be the last word in contemporary railroad design, he decided their name had to begin with Z. By chance, Budd had been reading the Canterbury Tales. In the Prologue, Chaucer writes, ‘When Zephyr also has, with his sweet breath, Quickened again . . .’ The reference to the god of the west wind settled the matter. Racing with or against the west wind, the first two Burlington streamliners were known as the Train of the Gods and the Train of the Goddesses. Their passenger cars were named after the Roman deities Apollo, Jupiter, Mars, Ceres, Diana, and Venus, evoking notions of beauty, power, authority and speed.

Luxury, speed and glamour

Until General Motors’ Electro-Motive Division got into its stride in the late 1930s, however, diesel could not produce anything approaching the horsepower of a big steam engine, restricting the number of cars that could be pulled and the on-board facilities provided. So the new streamline style was applied to the older technology, and it was a generation of mighty steam locomotives, modelled on sleek, wind-cheating lines, that powered the most glamorous streamliners. These included the Pennsylvania’s Broadway Limited, the Hiawathas of the Milwaukee Road, and the Southern Pacific’s Coast Daylight.

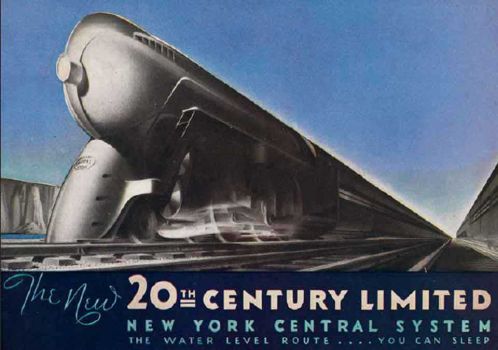

The brightest star of all was surely the 1938 edition of the New York Central’s 20th Century Limited. A seamless fusion of the highest-quality engineering, design and styling, this lengthy and magnificently equipped two-tone grey streamliner was ‘cleanlined’ by the celebrated industrial artist Henry Dreyfuss from the striking Trojan Helmet nose cone of Paul Kiefer’s imperious Class J3a Hudson steam locomotives to every last detail of the cars. Lettering, logo, livery. Cutlery, napery, crockery. Cocktail glasses, matchboxes, concealed lighting and refined décor. In terms of design, no train has bettered this mile-a-minute overnight New York–Chicago express.