The Regeneration of King’s Cross Station

Last Thursday, as a member of the Railway Heritage Trust Advisory Panel, I toured the works at King’s Cross, where Lewis Cubitt’s 1852 terminus is being restored and a new concourse added.

Up on the roof, as we walked along the valley gutter between the twin trainshed arches, we saw new plate-glass and solar-voltaic panels being installed. From the parapet of the station façade we could survey the entire battlefield of 19th-century railway rivalry, the plain engineering style of the Great Northern at King’s Cross facing the Gothic upstart of the Midland’s St Pancras across the road. Further west, now converted into a concrete hulk, lies the terminus of the North Western at Euston, on which the statue of Britannia atop St Pancras turns her back.

The Project Director for King’s Cross, Ian Fry, has all the ebullience of a railway engineer who knows he is creating the future. We have come a long way from the two original Departures and Arrivals platforms at King’s Cross, with sidings in between. Passenger numbers are now higher than they were in the 1920s, and are expected to continue rising, so a large new concourse is essential. It is being built in the space between King’s Cross and the Great Northern Hotel. As the last of the scaffolding is dismantled, the sweep of the honeycomb roof can be appreciated. ‘Jaw-dropping’ is what most visitors tell Fry, and it is. As a new railway building, it’s as good as you get, and Fry is justly proud of his achievement. Maybe his name will rank alongside Cubitt’s a hundred years from now.

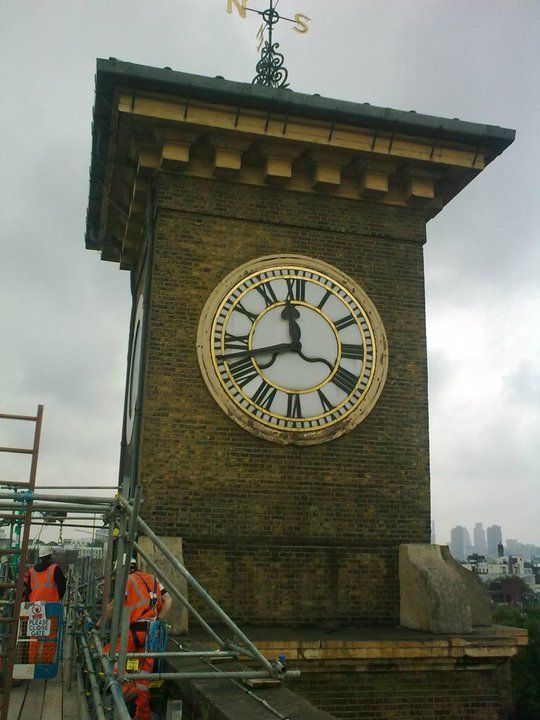

As we toured the station, I was ready to embrace the undeniable feats of engineering which have created underground service tunnels, sweeping passenger interchanges and concrete underpinning good enough to last a thousand years. The reglazed trainshed roofs will look stunning when all the gantries and covers have been removed. Part of the western range of buildings which was destroyed by a bomb in the Second World War is finally being rebuilt. The original booking office will be re-opened and the largest railway pub in Britain created further up the platform. Where necessary, panelled sash windows are being reinstated and the original station master’s office will once again become operational.

What I was uneasy about, when I saw the first drawings, I am still uneasy about. The new honeycomb-roofed concourse is a soaring success in its own right, but it is, as Ian Fry proclaimed, a new railway building, and as such it upstages Cubitt’s original design. Like a flying saucer, it has come to rest between two 19th-century developments, the western range of King’s Cross station and the back of the Great Northern Hotel, to which it is attached. It has nothing in common with either. Its steel girders cascade down in front of Cubitt’s western frontage, partly obscuring it. The mellow brick and sash windows of the original station are now seen through a glass screen. Two different idioms are jammed together, and inevitably they conflict. Cubitt’s idiom is Victorian domestic in brick, stone and wood, allied with engineering prowess in wrought iron and glass. Fry’s idiom is steel and concrete, and at the base of the new flying saucer you can see massive reinforced steel joists and concrete footings. Fine it may be, but it has nothing to do with the listed buildings it is supposed to complement.

The language of today’s engineer is steel and concrete, loads and functions. I do not doubt Fry’s satisfaction in the work he has undertaken to restore and reinstate so much of Cubitt’s station. He is to be congratulated for his enthusiasm and evident commitment. My concern is broader. Steel and concrete bring structural strength, and with strength comes superiority. It is only too easy for today’s engineers to assume that new is better. You can see the march of this belief in cities all over the world. Right here, there is an example of thoughtless modernism in the extension to St Pancras station, a glass box which bears no relation to the Barlow trainshed or the rich polychrome brickwork of the main station. The same is true of the Underground tunnels and concourses which are supposed to be part of the scheme.

Engineers and planners think it’s okay to jam a utilitarian box up against a soaring piece of architecture, but they are wrong. It will take decades more before this mistake is recognized for what it is, and by then our cities will be that much uglier than they have already become since the end of the Second World War. The extension of St Pancras is in everyday use, and I use it. The new concourse of King’s Cross will be opened early next year, and I will use that, too. But I will be hoping that, in a new age of enlightenment still to commence, architects and engineers will once again take a Grand Tour of the styles, master the subtleties of idiom and refrain from cramming unadorned steel and concrete down our throats.

There will be another test of architectural awareness when the 1970s concourse in front of King’s Cross is cleared away and an open plaza created. Two ventilation shafts from the Underground will remain. How should they be clothed and camouflaged? Here is an opportunity. Planners, engineers, architects and designers should ask themselves, what is the prevailing idiom of King’s Cross? What are the prevailing materials?

In designing a sign for the station entrance, they should ask the same questions. A quick look at the entrance to the re-opened St Pancras Hotel might provide a clue.

The views expressed here are my own and do not represent Railway Heritage Trust policy. To see pictures of the King’s Cross Regeneration Project, please visit our Facebook page (below) and click on Photos.

More Articles…

Scott of St Pancras · St Pancras Hotel